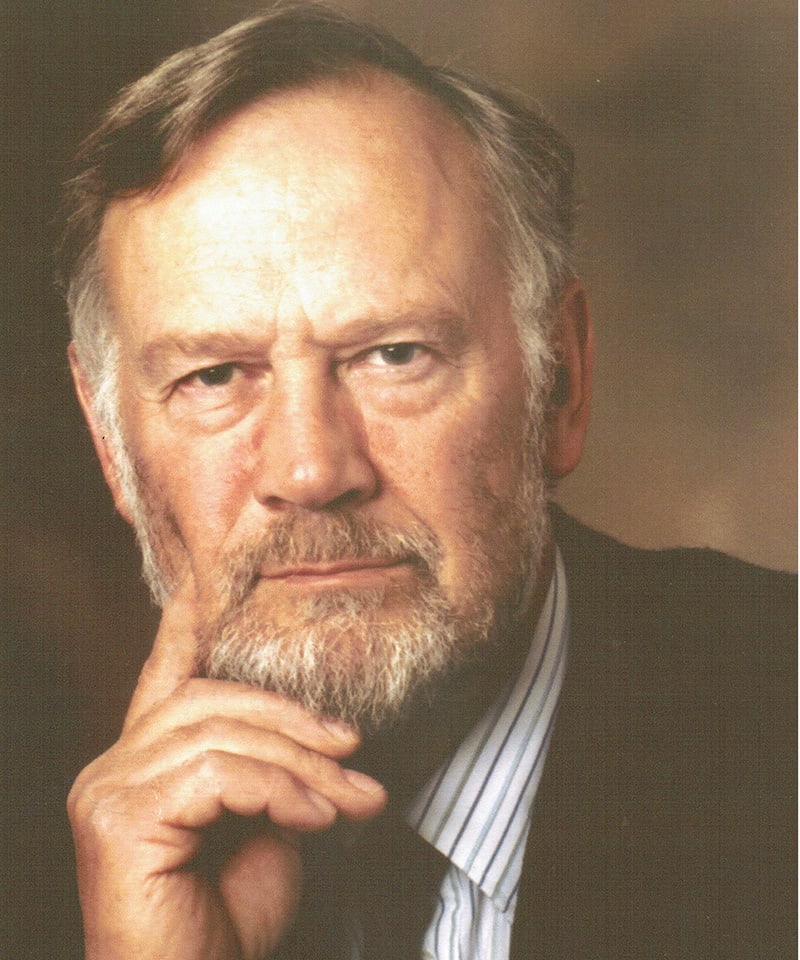

Alan Richens

1938 - 2021

I still remember vividly the moment I entered Alan Richens’ tiny office in the Department of Clinical Pharmacology of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, UK., on a clear skies morning of April 1976. I was a young medical school graduate with an interest in clinical pharmacology, and I had applied to spend a few months in his laboratory to learn techniques to measure blood levels of antiseizure medications (ASMs). He dedicated more than an hour of his time to me explaining how clinical pharmacology research had the potential to greatly improve the life of people with epilepsy. That conversation was the beginning of a relationship that changed my professional life. For the next five years, I worked under his supervision, first at the Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy and later at the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases at Queen Square, London. Although family reasons dictated my return to Italy in 1981, the strong friendship that we developed during those years persisted for the ensuing decades and kept us in contact until the last days of his life.

Alan Richens’ interest in epilepsy care and research originated by chance during a summer vacation in 1968, when he had just been appointed to a lecturership position in the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. That summer, he spent a brief period as a locum physician at the Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy which happened to be located a short bike ride from his home. While working in Chalfont, he was struck not only by the impact of severe recurring seizures on patients’ lives, but also by the massive burden of iatrogenic disease caused by chronic intake of ASMs. From that very moment, the medical treatment of epilepsy became the center of his professional life and the focus of his academic research.

Within a few years, his work was already widely recognized internationally, as evidenced by the honours received early in his career. He received the Paul Martini Prize in Clinical Pharmacology for his work on the pharmacokinetics of phenytoin in 1975, the Ambassador for Epilepsy Award in 1976, and the SKF Medal by the British Pharmacological Society in 1978. Again in 1978 he was the winner of the Michael Prize award as well as the first recipient of the Epilepsy Research Award for Outstanding Contributions to the Pharmacology of Antiepileptic Drugs, sponsored jointly by the ILAE and the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (ASPET). When in 1977, the National Hospital, Queen Square made a strategic decision to invest in epilepsy research, they called on Alan Richens to direct their newly established Clinical Pharmacology Unit. In 1981, he was appointed to the Chair of the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at the Welsh National School of Medicine in Cardiff, where he soon established an Epilepsy Unit with outpatient facilities as well as a service for EEG monitoring and drug level measurement. The Unit rapidly became a leading center for epilepsy research. As a tribute to his achievements and commitment to epilepsy care, the Welsh Epilepsy Centre in Cardiff was later renamed after him.

Alan Richens was a major driving force behind the impressive developments in the clinical pharmacology of epilepsy which took place in the 70s and the 80s. He made seminal contributions to elucidating the clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interaction profiles of ASMs and to defining the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of epilepsy. Together with Charles Pippenger, on the other side of the Atlantic, he was the first to highlight concerns with unacceptably large inter-laboratory variability in drug assays. The international external quality control scheme that he set up in the early 70s, which still exists to these days, played a key role in improving the reliability of methods used to measure serum levels of drugs used to treat epilepsy around the word. Alan Richens was also among the first to realize the value of the randomized controlled trial in evaluating the efficacy and safety of epilepsy treatments. He published in 1975 a landmark placebo-controlled adjunctive-therapy trial of valproate in patients with refractory epilepsy, and later he coordinated the highly influential EPITEG trial, which compared valproate with carbamazepine in 300 patients with newly diagnosed focal or generalized tonic-clonic seizures. He also played a key role in pivotal trials that led to the approval of vigabatrin, tiagabine and lamotrigine. Other areas where he made significant contributions include the development of methodologies for proof-of concept studies of ASMs, the assessment of the acute and chronic toxicity of ASMs, and the early exploration of the genetics of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.

Alan Richens was a superb teacher and lecturer, and his presentations and books stood out for their great educational value. I proudly keep in my library a signed copy of his 1976 paperback ‘Drug Treatment of Epilepsy (Monographs in Controlled Medicine)’, a real jewel in highlighting methodological issues which are critical in the correct interpretation of drug trials in epilepsy. That same year saw the first edition of ‘A Textbook of Epilepsy’, which he coedited with John Laidlaw.It became a highly successful comprehensive publication that through successive editions contributed to the education of epileptologists for the next two decades. His commentaries and review articles published in the 90s on topics such as generic substitution and rational polytherapy anticipated concepts and acquisitions that remain valid and timely to this very day.

All the above-referenced contributions were made over a period of less than three decades. In 1996, at the age of 58, he elected to retire from academic life and dedicate more time to his family and to other interests outside of the medical field. His commitment to promote epilepsy research, however, did not relent, and he served as Director of Epilepsy Research UK, for which he was a founding member, from 2003 to 2005, and then from 2005 to 2011 as a member of the Board of Trustees of the same charity. Before moving to Rugby and most recently to Bristol, he lived for several years in an old-style farmhouse on the edge of the Forest of Dean in Aylburton, Gloucestershire, trying to revive old breeds of livestock for the Rare Breeds Survival Trust.

He also cultivated a strong passion for vintage cars, and he enjoyed participating in rallies around the world, as far as New Zealand. He assembled an amazing collection of old cars and motorcycles, and wrote two books on Sunbeam motor cars, which he cherished. I recall visiting him in Rugby in 2002 and being driven in a glorious 1933 white Sunbeam 23.8 Sports Saloon to a nearby pub, where we had a wonderful lunch. However, when we were ready to drive back, the Sunbeam’s engine refused to start, much to his disappointment. When in June 2004, after his academic retirement, he was invited to the Cardiff City Hall to receive the ILAE UK Chapter Certificate of Excellence in Epilepsy Award, he offered to deliver a lecture entitled “Therapeutic Motoring”. Recalling his role as one of the founders of TDM in epilepsy, many attendees thought that there was a misspelling in the title and were startled when presented with a fascinating lecture about classic cars and the emotional feeling of traveling back in time.

During the last few years, his ill health restricted his motility which was painful for a man who had always lived a very active life. Both of us were lovers of nature, and from time to time we exchanged by email photos of our gardens and plants. In one of our latest exchanges, he shared a beautiful picture of Magnolia Soulangeana blossoming in his garden. No picture could better express the gentle character of a person who has been a leading light for me, as a mentor professionally and as a model of integrity and steady adherence to those values that count most in every other facet of life.

Emilio Perucca

Immediate Past President, ILAE

Subscribe to the ILAE Newsletter

To subscribe, please click on the button below.

Please send me information about ILAE activities and other

information of interest to the epilepsy community