Epigraph Vol. 21 Issue 4, Fall 2019

Six ways to maximize reproductive health in women with epilepsy

Worldwide, more than 15 million women of childbearing age have epilepsy. Each year about 600,000 of them become pregnant.

In the past, women with epilepsy were told not to get pregnant. Some were forcibly sterilized. Now, most women with epilepsy can have safe and healthy pregnancies; however, there are unique risks that can require careful management. Here are six ways that physicians can help optimize reproductive health in women with epilepsy.

Encourage planned pregnancy

Having a planned pregnancy makes everything easier and lowers many of the risks associated with maternal epilepsy, said Page Pennell, director of research at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and professor of neurology at Harvard University. Planning allows time to find the most effective and safest anti-epileptic drug (AED) — one that reduces or eliminates seizures while also minimizing risks to a fetus.

“Outcomes from planned pregnancies are much better,” said Pennell, current president of the American Epilepsy Society. “We have choices now that can bring down the risk of major congenital malformations, and we’re also finding that even the risks of obstetric complications —C-sections, premature deliveries —can be close to rates of the general population if women have good prenatal care.”

A 2019 study from the US-based Epilepsy Birth Control Registry found that unplanned pregnancies carried more than twice the risk of spontaneous fetal loss, compared with planned pregnancies. Of the pregnancies in the analysis, 67% were unplanned; the global incidence of unplanned pregnancy is approximately 44%, according to the World Health Organization.

A retrospective cohort study of 132 women with epilepsy in Japan found that women with planned pregnancies were less likely to have seizures during pregnancy and less likely to undergo medication changes. Unplanned pregnancies were not associated with greater risks of obstetric complications or neonatal outcomes, however.

Prescribe folic acid to girls and women of childbearing age

Folic acid supplements are recommended for all pregnant women to protect against certain types of birth defects. Although folic acid has not been shown to reduce the risks of major congenital malformations in the children of mothers with epilepsy, studies have found that folic acid may reduce risks for cognitive issues and autism characteristics.

The Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drug (NEAD) study group, led by Kimford Meador —clinical director of the Stanford Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and professor of neurology & neurosciences at Stanford University — found that preconceptional folic acid supplementation was associated with a higher IQ at age 6, compared with no supplementation. The difference, while modest (about 7 points), was statistically significant.

“Folate seems extra protective for women with epilepsy,” noted Meador during a session on epilepsy and pregnancy at ILAE’s 33rd International Epilepsy Congress in Bangkok. Without folic acid supplements, he said the risks of autism and language delay were more than 4 times those of children born to women without epilepsy. Taking folic acid drops the risk to about 1.7 times.

Folic acid may be more effective if started before conception—another advantage to planning a pregnancy. But starting supplements after conception can’t hurt, noted Pennell, given that the brain is developing throughout all three trimesters.

A 2019 survey of neurologists in 81 countries found that about 75% said they would recommend folic acid to women of childbearing age, though doses ranged from 0.4 mg/day to at least 4 mg/day. Most respondents had few pregnant patients; in the previous 12 months, 66% had seen 10 or fewer, and 15% saw none.

Though there’s not yet an evidence-based recommendation for folic acid dosage in women with epilepsy, Pennell said her personal strategy is to write a prescription for 1 mg, taken once a day. She says that anecdotally, she has noticed better adherence with a prescription, rather than a recommendation to purchase it over the counter.

Talk about birth control

“More than 50% of pregnancies in women with epilepsy are unplanned,” Pennell said; this is slightly higher than the percentage in the general population. The higher number may be partly due to the complex relationship between enzyme-inducing anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) and hormonal birth control methods. Co-prescription can lead to reduced blood levels of both drugs, reducing the effectiveness of the birth control method while also increasing the risk for seizures.

In addition, hormonal birth control reduces blood levels of lamotrigine, which could affect seizure control. There’s no conclusive evidence that lamotrigine reduces the protective effects of birth control.

“I think it falls to the neurologist to talk about birth control methods, because we’re the ones prescribing the drugs that affect birth control,” she said. “Very often, women will get their birth control from a primary care physician, who may not know about these types of interactions. There are lots of stories of women who say ‘Oh, my doctor never told me’” about interactions between birth control and AEDs.

Contraceptive counseling that includes recommendations can make a difference, but it’s not yet common. A 2016 study found that only 37% of women discussed contraception with their epilepsy care provider; the first visit was the most common time for this discussion. Women who received specific counseling about IUDs and their benefits (compared with hormonal contraceptives) tended to switch to an IUD more often than women who only got general counseling about interactions between AEDs and some forms of birth control.

Know the risks of valproate

Valproate (valproic acid, Depakote) increases the risk of certain birth defects, including heart defects, spina bifida, cleft lip, cleft palate and others. Children born of women taking valproate during pregnancy also tend to have poorer cognitive development, and a 2013 Danish registry study of more than 655,000 births showed increased risk for autism in children born to women taking valproate during pregnancy.

Torbjӧrn Tomson, professor of neurology and epileptology at Karolinska Institutet and head of the epilepsy section at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, is careful to note that despite the risks of valproate, some women require it. “There are women that do not respond to any other drug. For example, for idiopathic generalized epilepsy, valproate is superior,” he said. “There are women who need it. But they need to be fully informed and understand what the risks are.”

Regardless of a woman’s AED regimen, monitoring blood levels of medications can help reduce the risk of seizures, said Pennell. Some AEDs, such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam, appear to have faster clearance rates during pregnancy.

Read more about AEDs and pregnancy in a related Epigraph article.

Help dispel myths

Dispelling myths can help women be more confident about their pregnancies, and reduce anxiety. For example, some women (and doctors!) believe that seizure frequency will always increase during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. This is not necessarily the case. A European and International Registry of Antiepileptic Drugs in Pregnancy (EURAP) study found that in most women (50%-83%), seizure frequency will not change, and that 7% to 25% of women will see a decrease in seizures during pregnancy. EURAP did find that up to 33% of women will have an increase in seizures during pregnancy and that seizures during delivery were relatively rare (3.5% of cases, more common in women who had seizures during pregnancy).

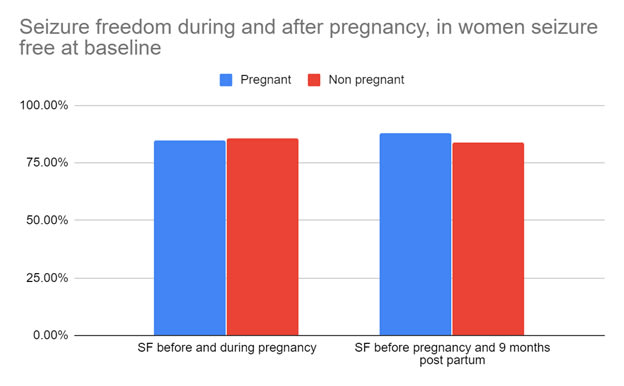

Data from the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study — an extension of the NEAD study — found that 46.7% of pregnant women were seizure-free in the 9 months before their pregnancy, compared with 45.0% of non-pregnant women who were seizure free in the 9 months before study enrollment. Among seizure-free women, there were no differences between pregnant and nonpregnant women in the 18 months after study enrollment (see chart).

A review of pregnancy-related knowledge and information needs among women with epilepsy found that while women were aware of many pregnancy-related issues, their knowledge of those issues and the actual risks involved often was lacking. Many women said they wanted to receive more information — particularly about AED risks — well in advance of planning a pregnancy.

A 2018 survey of women with epilepsy in German-speaking countries reinforced the idea that many women need more information about pregnancy and epilepsy. Of the 192 women who took the survey:

- 60% had talked with their neurologists about pregnancy-related issues.

- 46% did not believe that the majority of women with epilepsy give birth to healthy children

- 41% of those taking valproate were not aware of its association with malformations

- 38% of those taking enzyme-inducing AEDs were not aware that these drugs interact with oral contraceptives

Many women also believe they should stop taking AEDs during pregnancy to protect their growing baby. However, discontinuation is not recommended, as it carries multiple risks, including seizures and SUDEP. The EURAP analysis found that 63% of women did not require AED changes during pregnancy. For women concerned about the effects of AEDs on their pregnancy, a clear conversation about the risks and benefits can go a long way toward alleviating their fears.

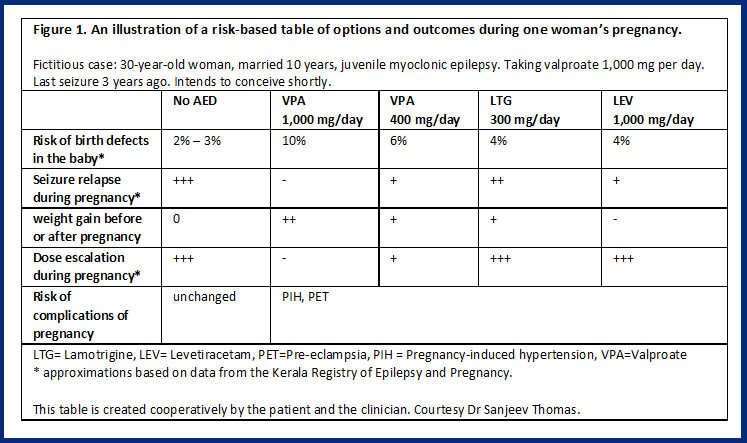

For the past several years, Sanjeev Thomas, chief of neurology at Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology in Thiruvananthapuram, India, sits down with his female patients before they become pregnant to discuss the risks and benefits of various choices. Each woman writes down her concerns — seizures during pregnancy, the risks of malformations — and Thomas talks about options to minimize risks while maximizing benefits. Thomas uses risk data from the Kerala Pregnancy Registry, which he manages.

Together, over 15 to 20 minutes, Thomas and his patient create a table that shows the risks and benefits to each choice (see Figure 1 for an example). Thomas says that this approach — a form of shared decision-making — not only helps women understand the process better, but also makes them more confident about their pregnancies and their health.

“When I used to give all this information to the patient in a talk, at the end they’d look at me and say, ‘Doctor, you know best; you please decide and we’ll follow what you say’,” said Thomas. “That means they’ve not understood anything. Now, with the risk table, that kind of response has decreased. I think they’re able to grasp the information and make their own decision.”

Provide reassurance

Thomas’ risk tables not only provide information, but also a form of reassurance. Women with epilepsy can be reassured that their journey is not drastically different than that of most other pregnant women, Pennell said.

To that end, said Meador, “We must be careful not to present all the risks and potentially negative outcomes” without reassurance, he said. “In any first pregnancy especially, women are anxious, and if they have epilepsy that anxiety is doubled, at least. Because people with epilepsy also tend to have anxiety as well, it’s so important to provide reassurance.”

Data from Pennell et al. 2018. Study included 461 women with epilepsy and compared seizure frequency before, during and after pregnancy (or before enrollment, months 1-9 of enrollment and months 10-18 of enrollment, for nonpregnant women). The women represented in the chart were seizure free at baseline.

Subscribe to the ILAE Newsletter

To subscribe, please click on the button below.

Please send me information about ILAE activities and other

information of interest to the epilepsy community