Epigraph Vol. 24 Issue 1, Winter 2022

Addressing anxiety in people with epilepsy: The power of the neurologist

By Nancy Volkers, ILAE communications officer

Cite this article: Volkers N. Addressing anxiety in people with epilepsy: The power of the neurologist. Epigraph. 2022;24(1):7-13.

Olivia Gatlin usually knows when a seizure is coming: She starts to get anxious. The feeling starts in her feet and moves to her neck. Sometimes she’s not sure if she’s experiencing an aura, or anxiety. In either case, the 42-year-old uses self-taught breathing exercises to calm herself.

But until recently, Gatlin had never discussed anxiety with her neurologist.

“I took it for granted that the anxiety was coming along with my seizures, and I was just going to have to deal with it,” she said.

The impact of anxiety

Studies estimate that some form of anxiety disorder affects at least 25% of people with epilepsy, yet anxiety is underdiagnosed and undertreated. More attention often is paid to depression, possibly because of the risk for suicide. However, anxiety disorders also can increase risk for suicide, said Coraline Hingray, Pôle Universitaire du Grand Nancy and Centre Psychothérapique de Nancy, France, during a session at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) Annual Meeting in 2021. Also, said Hingray, anxiety in people with epilepsy is a stronger influence on quality of life than either depression or seizure frequency. And it is associated with poorer epilepsy outcomes.

A recent study found that among people with newly diagnosed epilepsy, those screening positive for both anxiety and depression had 7 times the risk of recurrent seizures, despite treatment with anti-seizure medications (ASMs), compared with those who screened negative for both conditions.

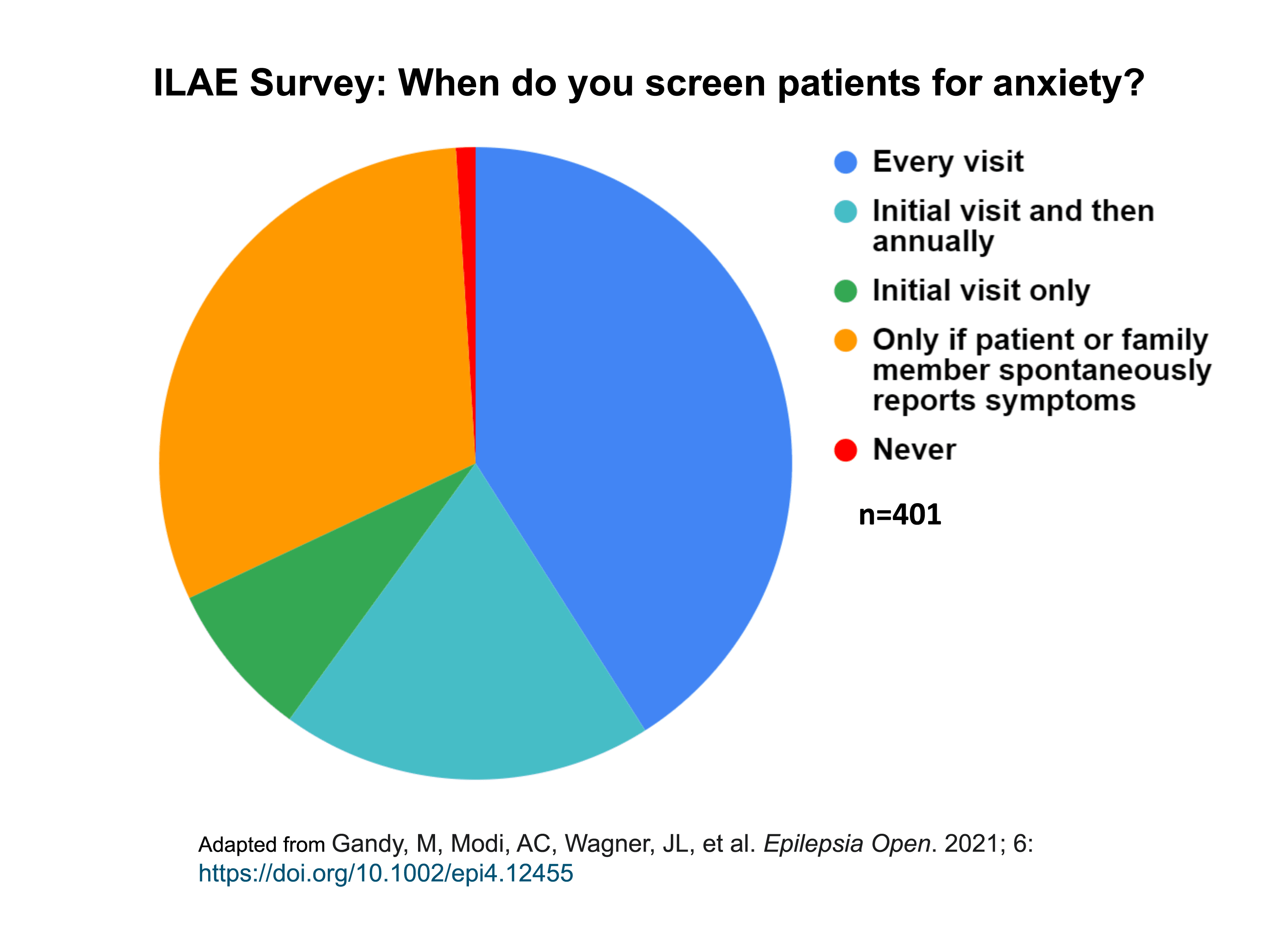

A 2021 survey by the ILAE Psychology Task Force found that only 41% of epilepsy care providers screened patients for anxiety at every visit. Another 1% never screened for anxiety, and 31% screened only if the patient or a family member spontaneously mentioned anxiety during a visit.

Bidirectional relationship

“There is a bidirectional relationship between anxiety and epilepsy,” said Heidi Munger Clary, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, USA, and co-chair of ILAE’s Integrated Mental Health Care Pathways Task Force. “People with anxiety are at greater risk for epilepsy, and people with epilepsy are more likely to develop anxiety. That is likely related to the same structures being involved in both conditions.”

Addressing anxiety in people with epilepsy can make a major difference, said Munger Clary. “It’s critical that we do what we can to address anxiety and depression. We talk about anxiety less, and the amount of expertise and comfort with managing it is lower,” she said. “But there is a big opportunity for us to impact care and improve lives.”

Screening for anxiety: A first step and a conversation starter

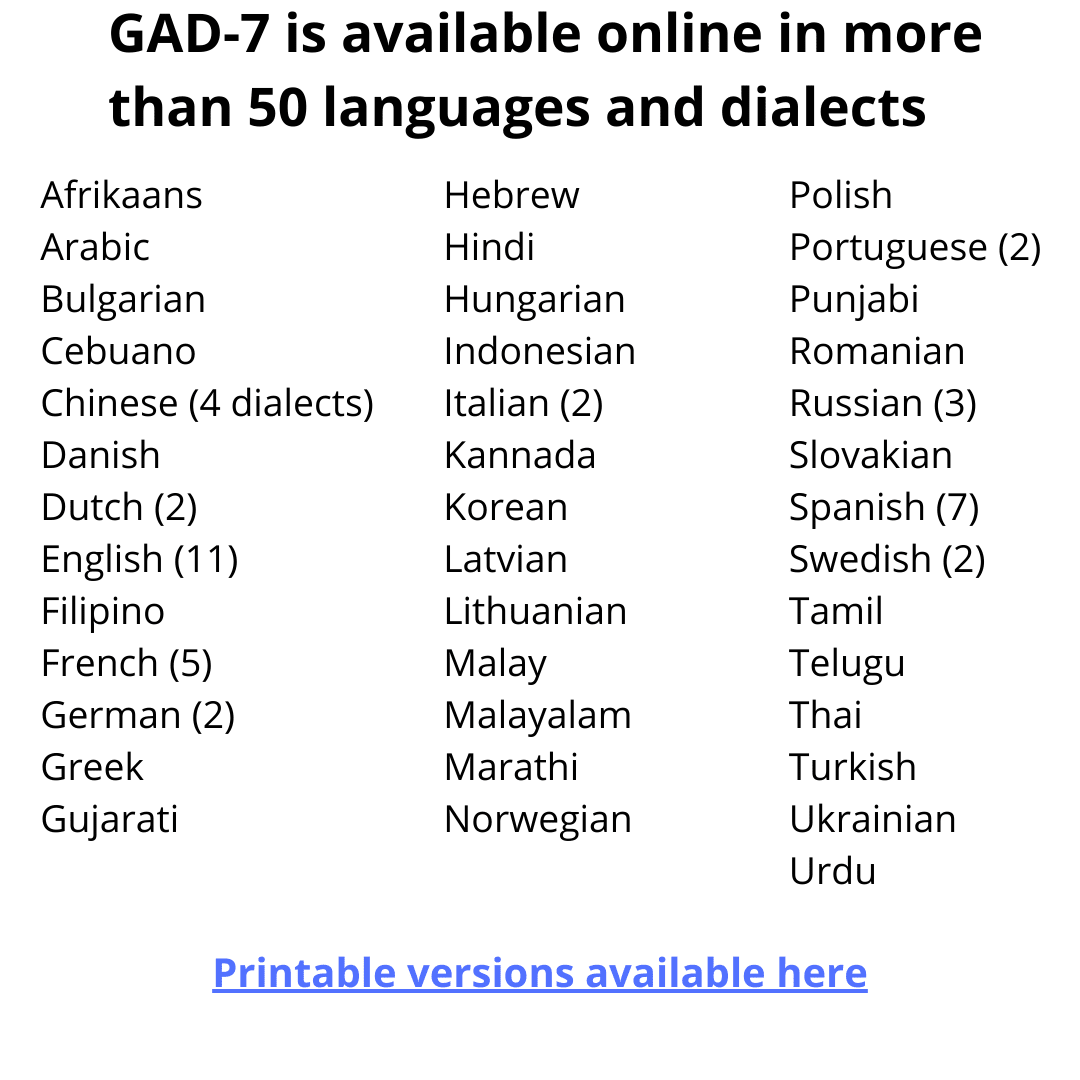

Many neurologists cite time constraints as a barrier to screening. The GAD-7 screening tool takes only a few minutes and can be completed in the waiting room. It’s used in the general population to screen for anxiety and has been validated in people with epilepsy.

GAD-7 is available online in more than 50 languages.

Printable versions of GAD-7 in English are available here and here.

This page provides a printable GAD-7 in French (Canada).

This page provides printable GAD-7 versions in Arabic, Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese, Hindi, Korean, Russian, Spanish, and Thai.

And an online, automatically scored, English version is available here (no log-in is required and no identifying information is collected)

GAD-2, a short version of GAD-7, appears just as effective in identifying anxiety in people with epilepsy. A score of 3 or more on the GAD-2 identifies generalized anxiety disorder at least 86% of the time.

GAD-2

|

Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems: |

Not at all |

Several days |

More than half the days |

Nearly every day |

|

Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Not being able to stop or control worrying |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

The Epilepsy Anxiety Survey Instrument (EASI-18) and its briefer counterpart, brEASI, are also anxiety screeners designed and validated in people with epilepsy. They are freely available in English and currently being translated and validated in other languages.

Offering a screening tool before an office visit is an excellent way to start a conversation about anxiety, said Munger Clary. If time or resource constraints prevent using a screener, she recommends asking a single question during the visit. “I might ask, ‘Are you having any challenges with mood?’ or ‘Are you having challenges with depression or anxiety?’,” she said. “Patients seem to respond well.”

Barriers to anxiety management

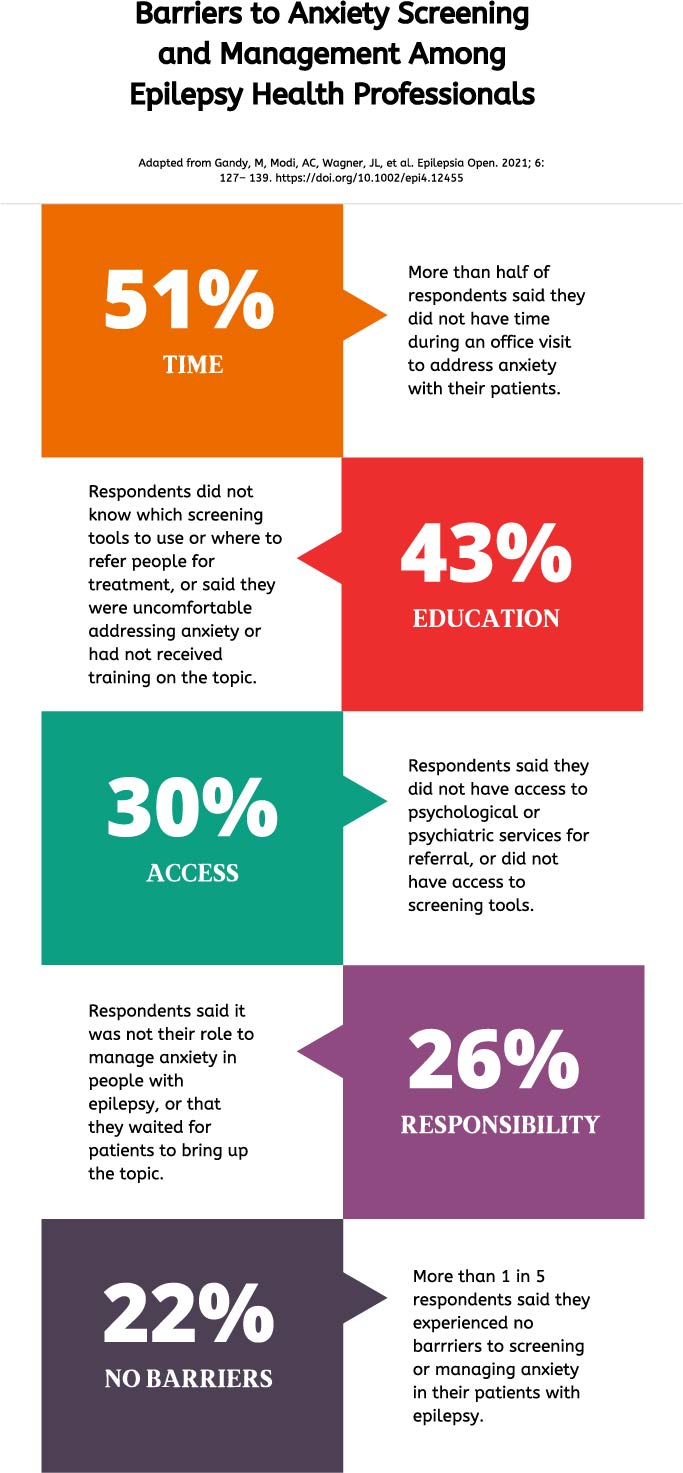

More than 93% of respondents to the ILAE Psychology Task Force survey agreed that the management of depression and anxiety is integral to the care of people with epilepsy, but only 40% agreed that they had adequate resources.

Guidelines, or the lack thereof, are another concern. “I think everyone recognizes that anxiety is common and problematic, but there aren’t integrated protocols on what to do,” said Milena Gandy, School of Psychological Sciences, Macquarie University, Australia. These barriers should not deter epilepsy care providers, said Gandy. “The psychosocial factors are potentially modifiable, whereas many of the medical factors aren’t. You can’t change the type of epilepsy people have, but you can help people modify the way they think, what they do, and how they understand their epilepsy.”

Types of anxiety

A 2011 consensus statement from the ILAE states that it’s essential to establish the relationship, if any, between the anxiety and the epilepsy. Anxiety can be any of several types, and many people experience more than one type:

- An interictal (between-seizures) anxiety disorder is the most common and is independent of seizure occurrence. It includes generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and others.

- A side effect of anti-seizure medication or a new development after epilepsy surgery

- Peri-ictal anxiety, which can occur up to 3 days before a seizure, during a seizure (aura), or up to 5 days after a seizure. This type is often underrecognized. Improved seizure control will reduce these anxiety symptoms.

Anxiety also can be associated with fear of seizure recurrence (seizure phobia), or a reaction to the diagnosis of epilepsy and the limitations associated with it.

Medication and counseling

Gatlin, who lives in North Carolina, USA, started medication after she began to have panic attacks in late 2021. The attacks started days after her first generalized tonic-clonic seizure. They come out of nowhere.

“I get pressure on my chest and my hands go numb,” she said. “You feel like you’re having a heart attack, like you’re going to die,” she said. “The first time I really discussed anxiety with my doctor was when I started having these attacks.”

Panic disorder may respond to any of several medications. Interictal anxiety often responds to medication or psychotherapy.

If the anxiety is pervasive and not seizure related, Munger Clary usually offers patients a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or selective norepinephrine uptake inhibitor (SNRI), if they aren’t already taking one. “I can do that on my own, and it’s pretty effective,” she said.

A 2016 review article in Epileptic Disorders discusses clinical, neurobiological, and pharmacological aspects of treating anxiety in people with epilepsy. The article includes recommendations for treatment of several anxiety disorders, including panic attacks, social anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

When it comes to psychotherapy, finding counselors who specialize in people with epilepsy, or in people with chronic conditions, would be ideal but isn’t necessary, said Munger Clary. “I think most people with epilepsy could benefit from a counselor with just general expertise,” she said.

Gandy agreed. “Seeing a psychologist and getting care is more important than finding someone who specializes in epilepsy, though in an ideal world you would want someone who has a bit of understanding of epilepsy and can tailor treatment to some of the unique challenges of seizures, as well as the stigma people face and what they can and can’t do.”

For more about cognitive behavioral therapy, a recommended treatment for some types of anxiety, see the callout box in this article.

Selecting treatment

Neurologists don’t necessarily need a definitive answer for how to manage someone’s anxiety, said Munger Clary. Often, the choice of treatment depends on what the person with epilepsy prefers. Having a conversation about wellness—healthy eating, good sleep patterns, physical activity—can help people begin to address anxiety before (or instead of) medication or counseling. Munger Clary published a study in 2021 in which 89% of participants were willing to try wellness options for their anxiety.

Connecting patients with an epilepsy support group or asking if they have one or two supportive family member or friends also can make a big difference, said Munger Clary. And for people with epilepsy-related anxiety, an epilepsy action plan can ease fears and establish a protocol.

Other options include educational handouts about relaxation techniques, suggestions for apps or online materials, a referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist, and epilepsy support groups. “And then there are alternative medicine types of opportunities--relaxation training, yoga,” said Munger Clary. “You can think through a lot of options and hopefully there’s something that can be done, if the person is looking for help.”

Who is responsible?

In the ILAE survey, 64% of epilepsy care providers said they weren’t responsible for managing anxiety in their epilepsy patients. This needs to change, said Adriana Bermeo Ovalle, Rush Medical Center, Chicago, USA. “Epilepsy providers should screen, diagnose, and pursue treatment of the psychiatric conditions that epilepsy patients face on a daily basis,” she said in a 2021 AES Annual Meeting session on patient care. “We don’t have the luxury of not making the diagnosis,” she said.

Bermeo Ovalle recommends that neurologists become familiar with SSRIs and SNRIs for anxiety.

“There are some intriguing data showing an improvement in seizure frequency when people with epilepsy are treated with SSRIs,” said Munger Clary. “There needs to be more research, of course, but it does raise the question—if the same brain structures are involved in both conditions, will we one day discover a drug that can treat both?”

|

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): What is it? CBT aims to change unhelpful patterns of thinking and behavior. It is based on the principle that learning coping skills can help not only with mental health, but also day-to-day functioning, including medication adherence and lifestyle modifications. CBT’s impact can be broad. “It is hard to manage a health condition and it requires skills – how do I problem-solve this, where do I ask for help with that, what can I do,” said Gandy. “Some people might have those skills naturally, but others might need a bit of help. That’s where CBT can come in.” One 2019 study randomized 200 people with epilepsy and depression to either an online CBT intervention or to usual care, with anxiety as a secondary outcome. People receiving CBT had significantly greater improvements in anxiety (as well as in depression, stress, social-occupational impairment, and epilepsy-related quality of life). At 3 months, they reported fewer illness-related days off work and fewer days hospitalized, compared with people in the control group. |

Online help for anxiety

Online, interactive courses are becoming more common for managing anxiety. Gandy runs a 10-week course that provides online psychoeducation similar to what would be given through in-person cognitive behavioral therapy, but with several advantages.

“The typical counseling session is 50 minutes; that’s a long time to pay attention,” Gandy said. “And often, people with epilepsy have additional attention challenges, as well as practical difficulties that make it difficult for them to keep in-person appointments. Online interventions can get around these barriers.”

Delivered over 10 weeks, the course offers 6 online lessons, worksheets, other resources and case studies, as well as brief weekly contact with a clinician through email and telephone.

Actionable advice on anxiety and epilepsy

Gatlin urged neurologists to be upfront with their patients about anxiety and epilepsy. “Doctors need to cover any and every side effect or other experience we could have,” she said. “People need to know that anxiety and panic could come along with the seizures, so they are prepared for it.”

Her advice to people with epilepsy: Pay attention to yourself. “Epilepsy has made me much better at listening to my body and evaluating myself,” said Gatlin. “There are ways to deal with anxiety, but first you have to be conscious of what’s happening to you.”

“The benefits of targeting mental health in people with epilepsy are wide reaching,” said Gandy. “You can help people’s quality of life as well as epilepsy outcomes.” She said ILAE’s Integrated Mental Health Care Pathways Task Force is studying what can be learned from other disciplines—such as oncology and cardiology—about integrating mental health care into epilepsy care.

“One in three patients that walks through your door are going to be anxious at some stage,” she said. “We know that depression and anxiety predict poorer outcomes. It’s not an easy thing to fix, but there’s no reason not to focus on it.”

ILAE has more information about screening tools for anxiety and depression in people with epilepsy.

Subscribe to the ILAE Newsletter

To subscribe, please click on the button below.

Please send me information about ILAE activities and other

information of interest to the epilepsy community