Epigraph Vol. 17 Issue 1, 2015

Building Infrastructure on the Road to Improving Epilepsy Care in Africa

There is no question that the lack of resources is a major, if not the major, impediment to even minimal appropriate epilepsy care in many regions and countries of the world. Although Africa is not alone in this regard, it is a problem that is common to most countries on the continent. At the recent African Epilepsy Congress in Cape Town, this topic was widely discussed. It was clear from the presentations and from spontaneous conversations that happened throughout the meeting that the major issues were shared by most countries and that many shared the same ideas for solving the problem.

At the Congress, I had the opportunity to speak with a number of epilepsy leaders from all corners of Africa regarding their thoughts about the basis for the problem and about improving the situation for the millions of Africans who suffer from epilepsy and its consequences. I spoke with Professor Charles Newton of Kenya, Professor Gallo Diop of Senegal, Dr Celestine Kaputu Kalala Malu of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Dr George Chagaluka of Malawi, Dr Omar Siddiqi of Zambia, Professor Jo Wilmshurst of South Africa and Professor Daliwonga Malazi of South Africa.

There was essentially universal agreement on the greatest need: trained personnel who understand the issues associated with epilepsy. As Professor Newton indicated, the greatest single need for epilepsy care is training of health workers especially in the peripheral clinics. Most treatment gaps occur in rural areas where health workers lack knowledge about the disease and its treatment, and many countries have only a handful of health care workers who are knowledgeable about epilepsy. Second on the list was access to antiepileptic drugs, which is limited by cost, availability (patients in many countries have only a limited choice of these drugs which have erratic availability) and knowledge of how to use them.

In addition to limited expertise and availability of effective medications, there is a simple lack of awareness that treatment exists. Professor Magazi noted that greater awareness about the disease and its treatment will go a long way to improving care. This issue looms larger the farther one is from urban settings where knowledge about modern medicine is often quite limited. Some of those interviewed indicated that this lack of awareness may be a far greater impediment than the potential costs of treatment. Professor Newton noted that the costs of seeing a physician and obtaining antiepileptic medications may not be much different than the fees of a traditional healer. However these comparisons can be difficult, as one requires cash and the other is often paid in goods. Paying for services also varies from country to country. In some countries, there are a few people who have private health insurance. In some countries there is no insurance and payment is entirely out of pocket. In a few, such as Malawi and Zambia, care is free to all at government hospitals. For those who don't have insurance in South Africa, there is expectation of payment, but payment is on a sliding scale, depending on the patient's resources.

To combat the widespread ignorance about the disease, a number of groups are actively developing epilepsy awareness programs. Professor Diop said that the Senegalese Epilepsy Association regularly provides information through radio programs and newspapers. In addition there are regular workshops about epilepsy in schools and to women's associations. They have also had several workshops with traditional healers. All of these efforts have resulted in a significant increase in hospital visits for seizures and epilepsy. The Kenya Association for the Welfare of people with Epilepsy (KAWE) has a number of programs to raise awareness, and there is a television melodrama that includes someone with epilepsy. Still utilization of resources is low and stigmatization is still high. According to Dr Malu the National League Against Epilepsy in the Democratic Republic of Congo is developing an awareness program that is in part aimed at politicians and other decision-makers. Epilepsy South Africa also has radio programs to increase awareness. Across the continent it is essential to reach the people in positions of influence, as they are the ones who must be reached if national infrastructure for epilepsy is to be improved. Dr Saddiqi told me that in Zambia the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) association has worked hard to increase awareness at the Ministry of Health, which has resulted in improved resources for epilepsy. Some of the countries have individualized awareness programs to educate patients, families and small groups. These programs involve personal contact, often with a social worker or nurse. However, as Professor Wilmshurst pointed out, even though these programs are effective, there are simply not enough trained people involved to reach everyone.

One of the greatest obstacles faced in improving epilepsy care throughout the region is the low priority it receives in the public health arena. This observation was a universal comment among all of the people whom I interviewed. Infectious disease, especially the well known HIV pandemic that affects millions of people in many African countries, is receiving greater attention because of the high mortality. But, as Professor Newton pointed out, there are other reasons as well. In Kenya, he explained that another reason for the low priority for epilepsy is the common perception of epilepsy, which is viewed with the associated stigma and belief that people affected by the disease have limited intellectual capacity. For these reasons the public health benefit of treatment will show little gain for the investment of national resources. However, it is not so bleak everywhere. Dr. Saddiqi explained that in Zambia, the awareness programs initiated by the local IBE group have convinced the health ministry that greater support was a good investment for the country.

Because the lack of human expertise is a major impediment to progress, training programs are essential to improving epilepsy care. There appears to be more variability across countries in the existence and nature of training resources. Some countries, such as Senegal, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa, have some neurologists and a few epilepsy specialists (although very few for the size of the population); others such as Malawi and Zambia have less than five each. In almost all instances, these specialists are concentrated in the major urban centers. There are neurology training programs in Senegal, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa. In Senegal there is a diploma program for epilepsy as part of advanced medical training, and in South Africa there are several epilepsy centers in the tertiary medical centers at which additional epilepsy training takes place. The amount of time dedicated to epilepsy education is limited for doctors in training. Similarly, training for nurses and medical officers may include a very basic introduction to epilepsy. KAWE in Kenya does provide some training for community health workers. Diagnostic facilities such as MRI and EEG are available on a limited basis, but again these are in the major population centers and hard to reach for many.

Although there is always the reaction to send physicians out of Africa to obtain the needed training, there was unanimity among the leaders with whom I spoke that such an approach is generally not useful. First, many who go abroad choose to stay abroad. Just as important, the training they receive outside of Africa has little relevance to many of the conditions they will encounter or to the resources they will have at home to do their work. All agreed that training should happen locally, and training is the key to solving the critical manpower shortage that is the basis for improving epilepsy care.

All of the African leaders look forward to the day when treatment is not limited by patient resources, poor access to medications, and the lack of expertise. What impressed me in my discussions at the Epilepsy Congress is the enthusiasm and dedication in the African epilepsy community. There was optimism tempered with the recognition of the current realities. It is clear that much progress has been made already, and that this progress is a good sign for the future.

About the Author

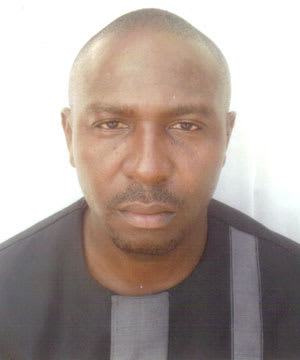

Dr Roland Chidi Ibekwe is a Senior Lecturer in Pediatrics at the University of Nigeria and Consultant Pediatrician at Child Neurology unit of the department of Pediatrics, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu. He is currently pursuing a Pediatric Neurology Fellowship at the Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and the University of Cape Town courtesy of the African Pediatric Fellowship Programme (APFP). He did his undergraduate training at the University of Port Harcourt and his postgraduate training in Pediatrics at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu.

Subscribe to the ILAE Newsletter

To subscribe, please click on the button below.

Please send me information about ILAE activities and other

information of interest to the epilepsy community