Epigraph Vol. 25 Issue 4, Fall 2023

Changing the game: Sports bra inventor led charge for more research on epilepsy in women

By Nancy Volkers, ILAE communications officer

Cite this article: Volkers N. Changing the game: Sports bra inventor led charge for more research on epilepsy in women. Epigraph 2023; 25(4): 86-91.

After inventing the first commercial sports bra in the 1970s, Lisa Lindahl leveraged her unique perspective as a business leader with epilepsy to increase research funding for and awareness of epilepsy-related issues in women.

To read more about Lisa Lindahl’s Jogbra® journey, read Part 1 of this series.

Lisa Lindahl enjoyed running; it made her feel strong and comfortable in her body. “I did not have a particularly healthy relationship with my body, because of my epilepsy,” she said.

But Lindahl didn’t enjoy the fact that in 1977, sports bras didn’t exist. That made for uncomfortable jogging.

“I wore a bra one size smaller than normal, but it didn’t help,” said Lindahl. After convincing her friend, costume designer Polly Smith to design a bra that was supportive, breathable, and non-chafing), Lindahl decided to turn her idea into a business.

“You know, I probably wouldn't have bothered with [the idea] if I didn't have to deal with epilepsy,” said Lindahl. “Earning a living can be complicated with that element in the mix. I couldn't drive, and employers could be anxious about hiring a person with epilepsy. I needed something so I could support myself. I thought, ‘I can make a little mail-order business out of my apartment.’”

Jogbra, Inc., rapidly became much more than a little mail-order business, growing into a highly successful company with Lindahl at the helm. After more than a dozen years, she and her co-owner chose to sell the company, and Lindahl bowed out after working a year or two with the new management.

With the invention of the sports bra, Lindahl had helped to change the world for millions of women. She didn’t know it, but she was about to change the world for millions more — through epilepsy advocacy.

Epilepsy advocacy begins

Lindahl didn’t know anyone else with epilepsy until her 40s, when she became involved with the Vermont chapter of the US Epilepsy Foundation. She had always been very private about her epilepsy. “I never wanted to put anyone out or feel like a burden. No one else understood, nor did most people care to understand.”

When Lindahl began doing speaking engagements, she realized that her life story could be an inspiration for other people with epilepsy.

“I would see people’s eyes spark with interest and comprehension and I’d think ‘Oh, my experience can be meaningful, helpful to others”,” said Lindahl. “And when the sports bra started being understood as a cultural phenomenon and I was named a feminist icon and people started calling me to talk about that, I finally realized, ‘Okay, this is a platform I can use to educate about living well with epilepsy. You can have seizures and not only earn a living, but do so on your own terms. In fact, I believe it can make you a more creative participant in life.’”

On board for women’s health

Her business expertise and epilepsy advocacy work led to a place on the national Epilepsy Foundation board. Lindahl joined in 1992.

“That was a whole new world,” she said. “It was an entire community of people familiar with and interested in epilepsy. I was not an oddball. All of these people — neurologists and nurses — dealt every day with it. I felt seen, known in a way I’d never before experienced. Yet I think I was the first person with epilepsy on that board. That’s when I realized that first, I could start talking about it, and second, I could start bitching about some of the more glaring needs — you know, like: ‘Why aren’t people paying attention to catamenial epilepsy? Why are women getting gaslighted?’”

Patricia O. Shafer, an epilepsy nurse specialist and consultant from Boston, also was a Foundation board member in the 1990s. “Lisa said, ‘You know, there’s something wrong in health care. Women are not being listened to. I’ve been dealing with some issues all of my life, and nobody’s addressing them.’”

Like many women, Lindahl had experienced changes in her seizures over her lifetime. Between puberty and menopause, her seizure pattern was clearly linked with her menstrual cycle.

“A week before my period, I would be at high risk for seizure activity,” said Lindahl. “Sometimes it would be a full-blown tonic-clonic; other times it would just be a lot of focal seizures. When I was running my company, I had to travel a lot, and I would try to not schedule travel during that high-risk time. But back then there were a lot of people in the epilepsy community who didn’t think catamenial epilepsy was a real thing.”

Influencing epilepsy research

Lindahl’s decades of business experience — borne from her need to find a flexible way to earn a living due to her epilepsy — now put her in a position to influence epilepsy research and care. She recruited a team of people at the Epilepsy Foundation to establish the Women and Epilepsy Initiative.

“In health care at that time, women’s issues were kind of pushed aside,” said Shafer. “And Lisa is saying look, there are many more issues other than what medications to give women with epilepsy when they’re pregnant. What about changes when we go through puberty, and through menopause? What about the impact on sexuality? And what about all the impacts on everyday life?”

Lindahl advised the rest of the board that women are the drivers of health care: They make appointments, drive children and parents to and from appointments, and manage prescriptions. At that time, women in the United States made 75% of all health care decisions and managed the spending of 67% of health care dollars. (This has not changed: in 2022, women controlled the spending of approximately 80% of all US health care dollars.)

“Lisa pointed out that women are the ones who make decisions about where health care dollars for their families are spent,” said Shafer. “Women are more powerful than they think.”

Lindahl wasn’t the only one making noise about the dearth of studies. In a 1994 textbook, Women and Epilepsy, Dr. Robert J. Gumnit was highly critical, writing: “The lack of scientific investigations into this important area is deplorable.”

History of exclusion

In the past, men were considered to be the “normal” study population, and researchers assumed that men and women would have the same responses to drugs — although women were considered “confounding” and more expensive to use in clinical research due to their regular hormonal fluctuations. In 1977 — ironically, the same year that Lindahl was developing what would become the Jogbra® — the US Food and Drug Administration banned women of childbearing age from participating in early-stage clinical trials in order to protect any developing fetus from potential harmful drug effects. The ban was lifted in 1993.

The Epilepsy Foundation held informal interest groups at its national conferences in 1993, 1994, and 1995. Women shared experiences of improper medical management of their epilepsy and misinformation about pregnancy, parenting, and menopause. Some women with epilepsy had been counseled to terminate their pregnancies or to have sterilization procedures.

“This was not going to be the Foundation creating a pamphlet and saying, ‘Look what we did for women’,” said Shafer. “The purpose here was awareness and education about women's health issues, empowerment of women with epilepsy, educating the health care providers, getting stakeholder groups together. We were looking at it from the ground up, trying to promote real advocacy and get programs going on a grassroots level.”

Finding the gaps

In April 1994, an ad hoc task force co-chaired by Lindahl and Dr. Martha Morrell convened for a weekend to develop a report on the status and needs for research on women and epilepsy. The group included people with epilepsy, their caregivers, representatives from the minority health community, officials from the National Institutes of Health and the US Food and Drug Administration, and researchers in neurology and obstetrics & gynecology.

The group’s report stated that little research was available to guide epilepsy diagnosis, seizure management, and quality of life issues in women. Major questions remained unanswered, including:

- What are the relationships between hormones and seizures at puberty, during the menstrual cycle, and at menopause?

- What are the fertility rates in women with epilepsy and do these differ by seizure type or epilepsy type?

- What are the risks, causes, and implications of reproductive endocrine disorders in women with epilepsy?

What are the relationships among epilepsy, menopause, and osteoporosis? - How can hormones be used to treat epilepsy?

The group recommended six key areas of activity: research, public education, professional education, medical management, advocacy, and funding. The Foundation board accepted the group’s recommendations in June 1994 and appointed a task force to oversee the implementation of the Women and Epilepsy Initiative.

A business plan for advocacy

Lindahl looked at the initiative through her entrepreneurial lens.

“She said okay, if we’re going to be successful, let’s create a business plan,” said Shafer. “We had different phases, and we created speakers’ bureaus throughout the country.”

Past initiatives tended to be physician driven and focused on patient education. “There would be a brochure and they would give it to people — and we said look, that doesn’t work,” said Shafer. Instead, the Initiative gathered input from health care professionals and women with epilepsy and created a packet of information.

“On one side of the packet were the issues written from the lay perspective for women, and on the other side they were written for health care professionals,” said Shafer. “We gave this to women with epilepsy with the goal that they share it with their doctors, their neurologist, their OB-GYN, their primary care provider. So we got inroads into different groups that way.”

Throughout 1994 and 1995, feasibility studies were conducted and the Foundation drafted proposals for establishing the Initiative as a national campaign on women’s health. Collaborations were established among advocates, researchers, clinicians, pharmaceutical companies, and government agencies. A 1996 forum solidified the goals of the Initiative, which was formally launched in 1997.

The Initiative was part of a groundswell of support for research and information on women’s health, including the establishment of the Office for Research on Women’s Health at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1991 and the change to the FDA policy banning childbearing-age women from early-stage clinical trials. In 1993, the US Congress passed a law ensuring that women and minorities be included in all clinical research.

A sea change in research

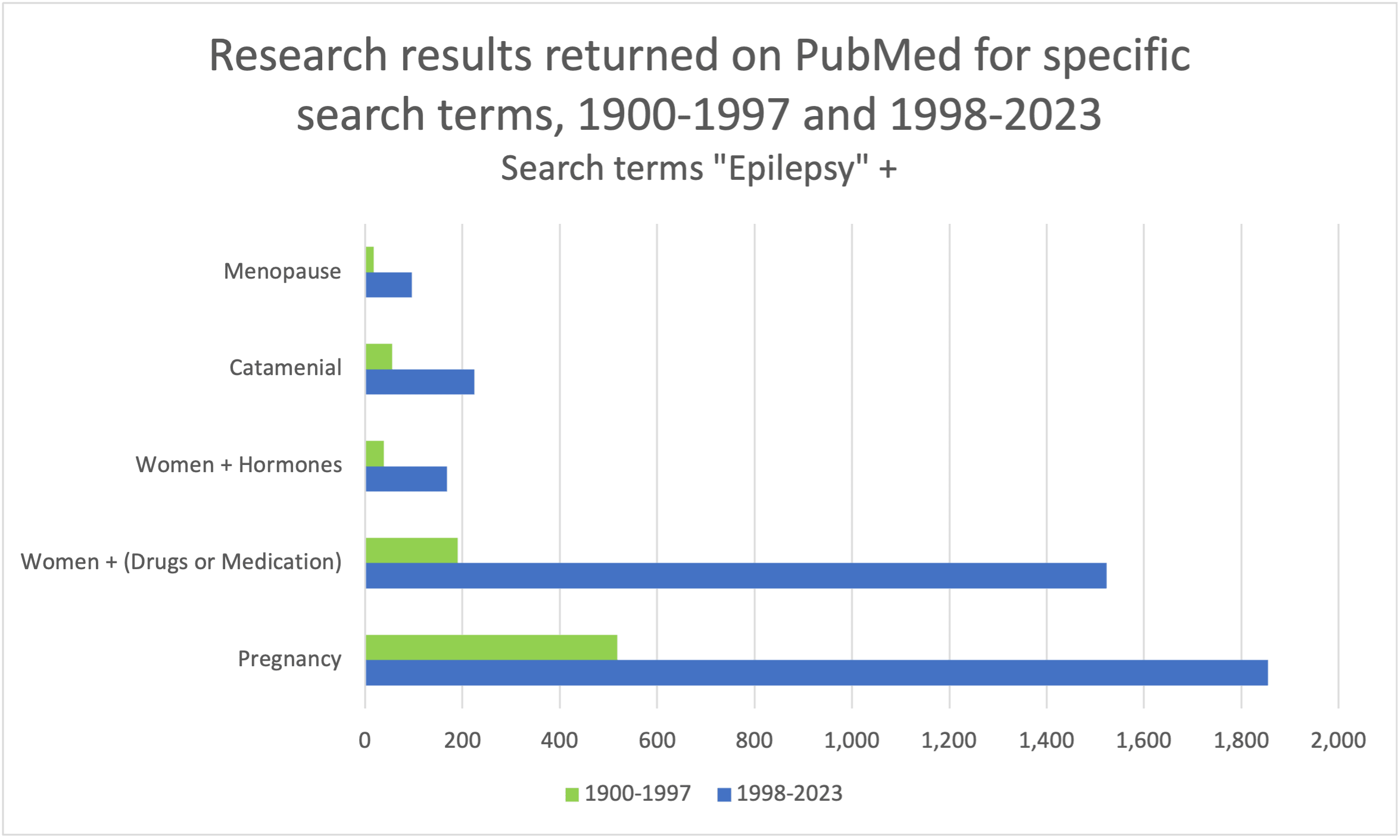

Since the mid-1990s, research on women, and on women with epilepsy, has increased dramatically. Published studies on epilepsy and pregnancy more than tripled, as did studies in related areas (see graph). As well, starting in the late 1990s, registries were established to facilitate research and understanding of pregnancy in women with epilepsy. Currently, there are pregnancy registries based in North America, Europe, India, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

For her efforts to improve the health and lives of women with epilepsy, Lindahl received the Epilepsy Foundation’s National Personal Achievement Award, as well as a US Congressional Commendation from Vermont Senator James Jeffords.

Lindahl stepped down from the Foundation board in 2001 after three terms — not because she wanted to, but due to term limits. “When I couldn't be on the board anymore, it made me very unhappy because I felt like my work wasn’t done,” she said in a 2020 interview with the National Museum of American History.

(In fact, her work wasn’t done. Lindahl invented a compression bra to manage lymphedema in people with breast cancer, and now holds 10 US patents. She also wrote and contributed to several books [see box].)

Multiple impacts

Lindahl sees her work with the Women and Epilepsy Initiative as her most significant life contribution. It wasn’t until she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2022 for the invention of the sports bra that she also acknowledged the impact of the Jogbra®.

“Until then, I understood and honored that others thought [the Jogbra®] was important, but I was also like ‘Yeah, whatever,’” said Lindahl. “But then I finally got it, how having access to a sports bra empowered so many girls and women. That’s when I could accept that it was significant. Because in my mind, I'm thinking, ‘Okay, but I did all that work with the Epilepsy Foundation!’”

|

Lisa Lindahl, philosopher and author After Jogbra, Inc. had been sold and Lindahl had become involved with epilepsy advocacy, she was in her lakeside home, looking out at the water. “I was thinking, ‘What really matters?’ You know, I’ve had this company, I’m on the epilepsy board, but what really matters? And the lake is shifting and changing; it’s springtime, and it’s so beautiful, and the answer that came was true beauty. Eternal, unchanging – true beauty. That’s what matters.” Her epiphany led Lindahl to California for graduate school, where in 2007 she earned a Master’s degree in culture and spirituality. She wrote her thesis on the importance of beauty, and then a book: Beauty as Action, (2017). “When I published it, no one was talking about this,” said Lindahl. “Now, people are talking about, noticing the importance of wonder and awe, how important it is to cultivate that childlike sense of wonder, and how little things are important. Wonder, awe – these are experiences of beauty. And now science is catching up. There are studies on the significant impact that experiencing beauty has on both our physical and mental health. Practicing True Beauty is healthy. And free!” In 2019, Lindahl published Unleash the Girls: The Untold Story of the Invention of the Sports Bra and How It Changed the World (and Me), which recounts the development of the sports bra from an idea in Lindahl’s apartment to an international sensation. Lindahl also wrote a chapter in Women with Epilepsy: A Handbook of Health and Treatment Issues (Columbia University, 2003), edited by Martha Morrell and Kerry Flynn. Other chapters are authored by noted epilepsy researchers, including Jacqueline French, Andrew Herzog, Kimford Meador, Steven Schacter, Patricia Shafer, and Simon Shorvon. |

Subscribe to the ILAE Newsletter

To subscribe, please click on the button below.

Please send me information about ILAE activities and other

information of interest to the epilepsy community